Learning Zone - Genealogy Mistakes to Avoid

In spring 2022 we began a social media series ‘Genealogy Mistakes to Avoid’. A number of people asked us to put these on our website so here it is. This is not a comprehensive list, and it wasn’t designed to be in order of importance, but hopefully this series of short posts will give you some inspiration and help you avoid some mistakes as you trace your Scottish heritage.

For more detailed information about some of these subjects visit our Learning Zone.

Not talking to relatives enough

Entering women with their married surname

Don’t copy other people’s research, and I am not just talking about Ancestry trees

Believing your family has always spelled your surname the same way

Believing the family story implicitly

Adding the same person to your tree multiple times

Not keeping a theory tree secret

Turning up unprepared at an archive

Missing the Scottish Indexes Conference

Using only the big-name websites!

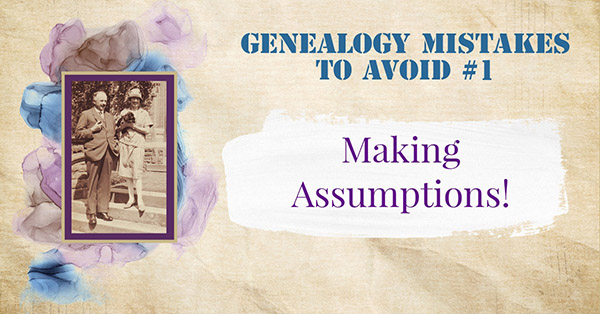

Don’t assume anything

It can be very frustrating when a Scottish birth certificate does not name the father. If the parents of a child were not married a father’s name would only be recorded if he presented himself to sign the register when the birth was registered or a court action led to his name being added.

Let’s say you find your family in the census, a husband, wife and three children. From 1851 in Scotland you will be told how each person relates to the head of the house; usually the husband. Therefore you will be told that the woman is the wife of the head and the children are his children; that’s right, his children. It would be easy to assume that all the children are biological children of both the husband and the wife but the census will not tell us if that’s the case or not. Of course, they often will be, but keep digging and find documents to support this.

Of course, in the 1841 census, we are not told any relationships at all so we need to be even more careful. We may be tempted to make assumptions when looking at other records too. When you are researching, ask yourself:

How do I know that?

Have I made an assumption or do I have evidence to support my research?

It’s OK to have a theory but don’t rest until you have the evidence.

Not looking at the next page

I was looking at a passenger list the other day. The first time I looked at it I thought I had read all the information. Later I went back to review it and realised there was more information on the next image. The relative in Scotland was listed on the second page! If you can, always look at the page before and the one after to make sure you have come to the end of the record. It’s a good habit to get into.

On ScotlandsPeople you will usually be charged for looking at the next page but if your family is split over two pages in the census you can ask for a refund. If they are at the top or bottom of the page check to see if you have the whole household. For example, is the top person listed as the head of the house? If they are at the foot of the page, are there two small lines indicating the end of the household? If not, the rest of the family may be over the page.

It’s not just passenger lists and census records this applies to. In some countries birth, marriage and death records may have something written on the back. This is less likely to happen in Scotland; the exception would be that a sibling may be listed on the previous or next page of a parish register (but this would be indexed).

If you can, look at the next and previous pages to make sure you have the entire record.

Not looking at a map

When we’re hunting for our family they can move from place to place. In fact, agricultural labourers may have moved every 6 months. It may not be too surprising that we find our ancestors have moved but where have they moved to? Does it make sense?

We might try to match up a family from Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland with a family in Campbeltown, Argyll, Scotland. If you are not familiar with Scottish geography this may seem OK, but checking the map will show you the great distances involved and reveal that it would not be an easy journey. Nothing is impossible, but make sure you are connecting the right families. For example, if you have your family in Huntly in 1861 then you think you have them in Campbeltown in 1871 check the 1861 census of Campbeltown. If you find the family there in 1861 it can’t be ‘your’ family.

The opposite is also true. A map could show you that places are very close together. Let's say you have a family in the 1841 census living in Weem Parish but you find the baptisms in the Parish of Killin. As this is a different parish and seemingly a good distance away, it could seem like the 'wrong' family. Looking at a map showing where the family were living and where the church is would show you that the children were baptised at the closest church even though it was in a different parish.

For old maps check out the National Library of Scotland. They have a great collection and they are all free to access.

This video is from the November 2023 Scottish Indexes Conference. These are free online events to help people connect with their Scottish roots. Chris has kindly agreed to make his presentation available for you.

Ignoring the occupation

When trying to match our family up with the records it can be a real challenge when they have common names and lots of cousins in the same parish also have the same names. It can be a real tangle.

Sometimes we’re so focused on the names we forget about the occupation. Although people did sometimes change their occupation, it’s fairly unlikely that a married man would change occupation from a stone mason to a shoemaker. Both of these occupations would require an apprenticeship. Our ancestors would have served as an apprentice as a teenager and perhaps into their early 20s before they got married. How would a married man with children afford to be able to serve an apprenticeship and switch professions as we can today?

Of course, some occupations are the same but described differently. A shoemaker in one record may be described as a cordiner in another. A shipwright may also be described as a joiner. Or you may find a grocer being described as a victualler. If you come across an occupation that is uncommon today, check out the Dictionaries of the Scots Language to discover what it was.

Not keeping a research log

This is one I think we will all be guilty of. We’re hunting down an ancestor, looking here, there and everywhere. We search newspapers on Findmypast then head to ScotlandsPeople and Ancestry making all sorts of searches; then we have to stop. We’re right in the middle of our research and we have to put the dinner on or go to bed! When we come back to our research we can’t remember what we’ve searched already and end up doing it all again.

I like to keep a simple research log. It doesn’t have to be complicated. You could write it in a notebook, use a spreadsheet or make a simple Google Doc. An electronic note is useful as you can paste the URLs of entries.

For example, let’s say I am searching the Kirk Session records on ScotlandsPeople. I may come across an entry which could be relevant but I’m not sure. I copy and paste the reference above the entry and put this in a Google Doc, then I copy the URL. The URL is the text in the address bar at the top of the page that will start https://www.scot…. Copy and paste the whole thing, even if it’s really long. I then make a quick note like “could be X, Y or Z person but not sure”.

I will also record what I have searched and by which terms. For example, if I am searching newspapers on the British Newspaper Archive or Findmypast I will record who I have searched for and by which spellings. I do this even if the search didn’t result in any interesting finds! I may also make notes of things I should search for next time.

This means if I have to break off halfway through my research I can pick up where I left off next time.

Not recording sources

I think sometimes we don’t record sources either because we don’t have time to do it properly or because we’re not sure how to do it.

I like to keep a simple research log. It doesn’t have to be complicated. You could write it in a notebook, use a spreadsheet or make a simple Google Doc. An electronic note is useful as you can paste the URLs of entries.

Learning how to do this in a standardised way can be very useful, even if you are not a professional genealogist. Strathclyde University has produced a step-by-step guide to source citation which you can access for free here.

Let’s be honest with ourselves though. If you are building out a side branch of your great aunt’s family you may not be inclined to spend too much time citing your sources. If only we all had that much time in the day!

Be pragmatic, it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. Let’s say your tree is on Ancestry or another website and you find a record on ScotlandsPeople. You could simply enter ‘ScotlandsPeople’ then copy and paste the title of the record given to you by ScotlandsPeople such as ‘1917 WILSON, GEORGE (Statutory Registers Marriages 848/ 6)’. This means that when you go back to your research you will have a basic note of the source of the record and if you share your tree with someone else they will also know where you got the information from.

Of course, it would be wonderful if we all did it ‘properly’ all the time but let’s just try to do something.

Not talking to relatives enough

This is one that tripped me up. I spoke to my family who were very helpful and headed off to do my research. I quite quickly got back to John Smith, born c 1845, but I couldn’t find his death certificate. With a name like John Smith it was quite a challenge! I spent ages looking for him to no avail.

One day I was having a conversation with the family and someone happened to mention Pennsylvania, I can’t remember why now. My mum said, “some of our family went there.” This was something my mum and my gran hadn’t mentioned when I had asked about the family. It turns out that John Smith and many of his children emigrated to Pennsylvania. My great-grandmother was John’s daughter and she stayed here in Scotland.

My great-great-grandfather, John Smith, died in 1911 and is buried in Hewitt's Cemetery, Rices Landing, Greene County, Pennsylvania.

This taught me a valuable lesson. Talk to the family, do some research then go back and talk to them again. You may learn more each time.

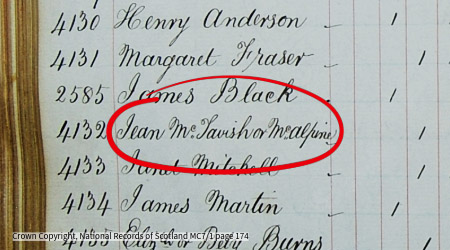

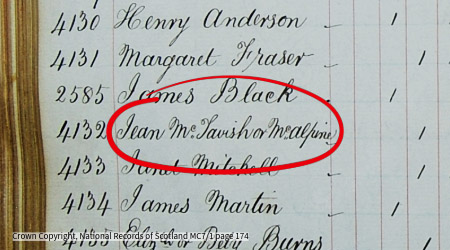

Entering women with their married surname

I cannot stress this one enough. Even if you don’t know a woman’s maiden surname do not use their married surname in your tree; leave it blank and don’t put ‘unknown’. Even if you are asking for help, always use a woman’s maiden surname and don’t move it to a ‘middle name’ position.

There are a few reasons for this. First of all, you are just going to confuse everyone. It’s quite possible that two people with the same surname married each other so if you have John Smith with a wife named Jane Smith we’re all going to think that was her maiden surname.

Also, the clever computer software at Ancestry and Findmypast that give us handy hints will look for marriages of a Smith to a Smith. You could miss a vital record.

This is true the world over, but there is an extra reason to do so in Scotland. It was very common for women to use their maiden surname throughout their life, even after marriage. A widow will often be recorded in the census under her maiden surname. If a woman left a will, it will almost always be recorded under her maiden surname. In early records, her married surname may not be included at all.

Maiden Surnames in Scotland |

Research Techniques |

Scottish Paternity Index |

New to Scottish Indexes? |

Maiden Surnames in Scotland |

Research Techniques |

Scottish Paternity Index |

New to Scottish Indexes? |

Labelling photos ‘Uncle Jim’

When you are recording who is in a photo be as precise as possible. If you describe someone as ‘Uncle Jim’, the person looking at this will need to know who made the note and which side of that person’s family the photo is from.

If, however, you put “James (Jim) Wilson (1845-1921), son of John Wilson and Agnes Smith” that will clearly identify the person.

When it comes to how to label photos there are various ways. It’s good to make a digital copy so that if the originals are damaged in any way you have a copy. It’s easy to rename a digital file and you can add as much information as you want to.

For the originals, you could invest in some high-quality acid-free albums to protect the photos. Try not to touch them as this can degrade them. You could buy an album where you can write on the album and not the photo. Whatever you do, don’t write on the back so hard that it dents the photo! Also, be careful you don’t use ink that will damage the photo.

Do some research, think it through and come up with a plan that works for you.

Don’t copy other people’s research, and I am not just talking about Ancestry trees

If you have an online tree you will get hints that someone else is researching your family. This can be really useful. Another branch of the family may have photos they can share or you could compare your DNA results. It’s great to connect with distant cousins.

When it comes to adding their research to your tree though, don’t! I was going to say be cautious but actually just don’t do it. It’s a slippery slope. If they have a well constructed and sourced tree you will be able to look at the original sources and add these to your tree. We all make mistakes in our research, if we copy another tree we could be multiplying a mistake.

It’s not just online trees. There are many printed genealogies, some of which were very well researched. Of course, they could have been compiled before the era of computers when records had to be searched by hand and not all records were public. Although these can provide helpful hints, they are not original sources.

Trace your own family history source by source, ancestor by ancestor.

Not checking the address

When a person dies in an institution, such as a hospital or a poorhouse, the institution is not always named, rather the street address is given. In Glasgow, if you see ‘133 Balornock Road’ that is in fact Stobhill Hospital. Always have a quick google of the address on a death certificate.

If the person died in an institution you could be able to find more records. It’s worth following it through to see what else you can discover.

Mental Health Records in Scotland |

Scottish Prison Records |

Civil Registration in Scotland |

Poor Relief Records Index |

Mental Health Records in Scotland |

Scottish Prison Records |

Civil Registration in Scotland |

Poor Relief Records Index |

Believing your family has always spelled your surname the same way

Most of our ancestors were more concerned about putting food on the table than how their name was spelled. The clerk recording the record may have decided how the name should be recorded based on their own experience or on what they heard. This means that we will see the same surname spelled in a whole variety of ways.

Not evaluating hints

If you have an online tree you may get record hints. I find them quite useful as the clever computer algorithms find records I may not have looked for. It’s important, however, to evaluate the hint; after all, it is just a hint.

Always click in and view the original record, check the transcription and compare it with what you know about your family. To do this it can be helpful to have two screens. Here in the office, my PC has two screens but if I am in the living room working on my own family I use my phone and my tablet. That way I have my tree on one device and the record hint on the other. Before you accept the hint, check it out for yourself.

Believing the family story implicitly

Let's face it, we all love a good story. Some stories seem to get better with each telling; does the fish your uncle caught get 3 pounds heavier every time he talks about it? It’s easy for stories to be embellished and exaggerated.

Also, some families told a story to cover the truth. In days gone by, many people were embarrassed about mental health issues and unmarried mothers. Stories could have been invented to cover a secret. If your gran was told her mother died young but you can’t find the death certificate, broaden your search. If someone was committed to an asylum the children may have been told that they had died.

If you can’t find an ancestor’s birth certificate, look under their mother’s maiden surname. The child may have been born before she was married.

Family stories are good, and fun to share and record: just remember to check the evidence and be prepared to discover the unexpected.

Adding the same person to your tree multiple times

We may be familiar with the fact that the name Elizabeth can be recorded as Lizzie or Betty, but did you know Jean and Jane are also interchangeable? As are Janet and Jessie. Think carefully when adding children of a couple and make sure you don’t add the same person three times with variations of the same name.

Not researching siblings

Sometimes we’re so focused on our direct ancestors that we forget about their siblings. The thing is, tracing them can be a great help. For example, we may find a parent living with a sibling in the census which could be a great clue.

Even digging further into other records can be a great help. For example, poor relief records may tell us where a person is from and where their parents are from/where they are living. Building out our family tree can help us trace our direct ancestors too.

Not keeping a theory tree secret

Theory trees can be really helpful if you have a brick wall or you are trying to work out how you connect to a person you share a DNA match with. We may be working on our research but we’ve not worked out all the kinks and added all our sources. This could confuse people, especially the inexperienced. If we keep our tree ‘secret’ or ‘unlisted’ we'll have all the benefits of an online tree without confusing people.

Turning up unprepared at an archive

Many archives keep records off-site. This means we need to give the archive some notice before we visit so that they can have the records ready for us to consult.

Many archives will have an online catalogue, but even then it’s worth emailing and briefly explaining the goal of your research. The team at the archive may be able to make some suggestions as to which records would be useful.

Make a plan before you go. List the records you want to consult and who you are looking for. I like to do this in a notepad (old-fashioned I know), so that I can use my tablet to see my family tree and my phone to take photos (if permitted).

Not all archives have WiFi and the mobile signal may not be very good. Make sure you have your tree offline or on paper. If you are taking a tablet or laptop you could also have a digital copy of the records you have already found so you can check them as you go.

Read carefully any instructions the archive gives you and let them know about any access requirements before you visit. For example, there may be restrictions on the size of bag you can take into the archive and you will probably not be permitted to use a pen. You may also need a reader’s ticket and to get this you may need proof of address and photographic ID. The archive will tell you their requirements so read carefully any instructions before you turn up.

The Scottish Council on Archives have a handy map of Scottish archives so that you can plan your research journey: click here to view the map.

Not organising certificates

There are any number of ways to file your certificates and other source material. You could have physical records in a binder or you could keep everything on the computer. Find a way that works for you and stick to a system.

We obviously have a lot of source material that we use for indexing and researching other people’s trees. We like to use the archive system where the original record is held. For example, we have a folder for the National Records of Scotland (NRS). Let’s say I was looking for Melrose Kirk Session - Minutes and Register of deaths (Mort Roll) 1668-1781. The NRS has given this item the reference CH2/386/2. I have filed a digital copy of this within our NRS folder, then in 002, then 0386 and finally in folder 002.

Another way to do it is to keep all records about one generation of the family in a separate folder. If you are only doing your own research this can be a good option.

There is no right or wrong but you do need to be organised and you need a system then you need to stick to it. While we’re on the subject of sources, it’s also a good idea to download key documents from subscription websites. If your subscription lapses or records are moved to a more expensive subscription you don’t have access to, it’s best to have them downloaded.

Not making a backup

Think of all the hours you have spent on your family tree and now think about how you would feel if you lost your research! Please make a backup.

There are various ways to make a backup. First of all, let’s think about your tree. If you have an online tree you can download a file called a GEDCOM. This is a standard file for genealogical data and can be opened by all (I think) genealogy software. Keep a copy on your laptop so that if you lose access to your online tree you have a basic copy.

If you work offline and keep your tree on your PC you could keep a copy of the GEDCOM on a memory stick as a backup or store it in the cloud as a backup.

When it comes to documents there are again various options for backup. Even if you have saved a record to your laptop ScotlandsPeople will keep a copy for you which you can access in 'Saved Images'.

It could be worth getting a portable external hard drive. This is a great way to store a backup but it will also be a great help if you buy a new laptop. If you work on a tablet an external hard drive can be useful as it will store more images than your tablet and you can then access them on a tablet or your laptop.

There are cloud storage options and these can be good but think about the long-term cost, not just the immediate cost.

Of course, you should always check with the archive’s terms and conditions when it comes to making copies of their records.

Mixing up the cousins

The most commonly used Scottish naming pattern was as follows:

1st son named after father's father

2nd son named after mother's father

3rd son named after father

1st daughter named after mother's mother

2nd daughter named after father's mother

3rd daughter named after mother

This means that John Grieve and Agnes Smith may have named their children:

William Grieve

Jean Grieve

Robert Grieve

Ann Grieve

John Grieve

Agnes Grieve

William would haved name his eldest son John and so would Robert. There would now be two John Grieves who were cousins. They may well have been about the same age and born in the same place. In fact, we could end up finding even more!

Take your time and work through it, building out the family so you can disentangle all the cousins.

Missing the Scottish Indexes Conference

We start our conferences at 7 am UK time and keep going until 11 pm UK time, showing every presentation twice. Why do we do this? So that wherever you are in the world you will have the opportunity to join us live and ask our experts a question.

You will be able to learn about a variety of aspects of Scottish family history. Genealogists will present case studies and share with you tips on how to use a variety of records for your family history research. Best of all, it’s free!

Using only the big-name websites!

There is no doubt that online genealogy with Findmypast and Ancestry would be very tough. Also here in Scotland, we have ScotlandsPeople; you can’t research Scottish ancestors without it. However, don’t limit yourself to these big-name sites.

Our own website, scottishindexes.com, has pre-1855 BMDs that ScotlandsPeople do not have. We also have indexes to records that are not on their websites such as criminal records, paternity records and health records.

Many archives also have information and indexes online. For example, Dumfries and Galloway Council Archives have a free index to Dumfries Kirk Session and Presbytery Minutes 1687-1838. They also have indexes to criminal records, the Dumfries Industrial School and much more.

Find the archive that covers the area your ancestor lived and you may find something helpful. Also, websites such as GENUKI are very helpful. It is a "virtual reference library" of genealogical information for the UK & Ireland, which can be great if you don’t know which parish a village was in, or which county that’s in. They also link to other websites, some more obscure, which have helpful indexes and resources for a specific area.

There’s a lot more online than you can find on the big genealogy websites.